Government cuts of £90m have forced the Open University to raise its fees, pricing thousands out of the market. Meanwhile, MPs complain about adult literacy figures, says Laura McInerney

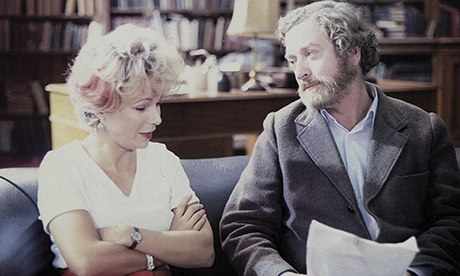

Still from the film Educating Rita (1983)

starring Julie Walters and Michael Caine. Is it getting too expensive for mature

students to get the education they missed out on earlier? Photograph: Ronald

Grant Archive

If heaven is indeed a place

on earth, I'd put money on it being an Open University

graduation ceremony.

There's nothing quite so electrifying as watching families

jump to their feet when mum, dad, or even great-gran takes to the stage. The

years of juggled childcare, jobs and family finances melt away as the graduate

beams down from the stage, amazed that their moment has come. And in the

audience you see the cavalry: the proud partner who poured endless cups of tea,

the parents who babysat, the children who hugged mum the morning of her exams

and almost made her cry when they said: "We love you whatever". This is the

stuff that makes the Open University great, but I fear the government is

treading all over it.

Last month, in a mawkish magazine article,

Michael Gove used the

analogy of Educating Rita (pictured), a film about a young woman from Liverpool

studying for an Open University degree, to argue that his education reforms are

helping children to get a better life. He nobly noted that children only have

"one chance" at school. Though true, it remains the case that no matter how hard

their teachers try, not every child will walk a simple path from school to

university and into the perfect job. Life gets in the way. I've taught umpteen

students whose lives

fell apart at 18 due to the death of parents, unexpected pregnancies, being

kicked out of home. University at that moment was simply not an option despite

my best persuasive efforts. In reserve, however, was always my Open Uni trump

card.

Imagine, then, how I felt

last year when sitting in Wagamama with an ex-student desperately wanting to

study now her life had settled down. As the sole carer of a younger sibling, she

was terrified by the thought of debt. I played the OU card. Their modules cost

only a few hundred pounds, I argued, less than the cost of one CD per week. "No

one buys CDs any more Miss," she said. "Fine, the cost of a mobile top-up, or a

coat from Primark!" Intent on convincing her, I summoned the OU webpage to my

phone, and waved it at her in excitement. Then my heart sank. Full-time OU

degrees in England now cost £5,000

a year. That's a lot of coats.

This is not the Open

University's fault. In Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, half-time modules

are only £700. But government cuts of £90m to the OU in England have forced

an increase. And it's not just the OU. Last week, the vice-chancellor of

Oxford University argued that it should be allowed to charge £16,000

per year. For a three-year degree, that raises a £48,000 bill before you

even start. A wannabe-educated Rita could buy a house in Bootle for that

money.

Sadly, Labour is proving ineffective at poking the government on this point. Liberal Democrats shut down conversations about it, terrified it may remind voters of their broken promises. Universities are under the remit of the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills, where the focus is predominantly on the recession. Thankfully, Matthew Hancock was appointed last week to a new role as minister for skills and enterprise, which will see him shared between BIS and the education department, suggesting there may be more will to start tackling the problems of adult learners.

To ensure this happens,

here is my plea. Every time the government repeats its mantra that the Wolf

recommendations on vocational education were fully implemented, Labour must ask

what happened to the guarantee that people who left school at 16 could retain

credit for three more years of education. When government MPs complain about adult

literacy, demand to know how it is being improved for adults who are in work

right now. And each time university is mentioned, emphasise that last year

mature student university applications plunged

by 14%. That is 18,000 fewer Ritas in university than in 2012 – and the

government cannot shirk responsibility for this one.

People who slipped through

the education net first time around do not need mawkish sentimentality. They

need low-cost options for accessing higher

education. If they, and their families, have the determination to do all the

rest of the hard work, the least they can expect is that politicians on both

sides will fight to support them.

Guardian