I’ve come across something which frightens me. As I wrote almost a week ago, one of the DWP’s (Department of Work and Pensions) own reports told it that sanctions were not only widely damaging, unfair and ineffective, but actually impaired people’s chances of finding work – and yet the DWP increased the number of sanctions (immediate suspension of benefits) applied to jobseekers by more than 47% in most recent 12-month period for which figures are available.

This increase – in the year up to October 2012 – took the total number of sanctions applied to a record 778,000. New figures were due to be published last month – but the DWP has delayed their release indefinitely. The reasons given for the delay were nebulous – but the previous rates of increase and the fact that new rules kicked in in October that could only accelerate the rate of increase make it extremely likely that the figures are so hideous that even this government is afraid to put them out there without some kind of recalculation to make them look less damning.

All this is obscene enough, but what has frightened me is another report by the DWP. This one dates back to 2006 and was commissioned by the previous Labour government. But before we look at that, we need a little background.

In September last year, Work and Pensions Minister Mark Hoban – a Tory whose crassness and insensitivity makes even that of many of his colleagues seem mild by comparison – answered questions on the new sanction regime that was due to begin in October. Among the answers he gave was this:

I was asked why we are introducing a three-year sanction. As I said, it will apply only in the most extreme cases, where claimants have serially and deliberately breached their most important requirements, and where other sanctions have not worked to change behaviour. We anticipate that few claimants will be subject to this length of sanction, but we do believe it is necessary to act as a deterrent and to ensure compliance with the conditionality regime, which is critical to help these claimants back into work.In order to get through the debate, Hoban was prepared to cast this 3-year sanction option as unlikely to be used at all, and even then only on the most persistent and intransigent ‘serial offenders’. However, this did not tally with another Hoban’s statements in the same debate:

Sanctions will also be tougher for those who repeatedly fail to meet their requirements, because the length of sanction will increase with each failure. The longest sanctions will apply to non-compliance with requirements directly linked to employment, such as leaving a job voluntarily, refusing to take up a job offer or failing to participate in mandatory work experience. For such failures, the sanction periods will be: 13 weeks for the first failure; 26 weeks for a second failure within a year of the previous one; and 156 weeks—3 years—for a third, or further, failure within a year of a previous failure that led to either a 26-week or 156-week sanction.Nothing there about ‘only in the most extreme cases’ – just ‘those who repeatedly fail’. ‘Repeatedly’ is a cover-all word and applies to simply failing to meet a requirement three times, which is exactly what the regulations, when they were published by the DWP a month or so later, said and continue to say:

Under the new regime:

Higher level sanctions (for example for leaving a job voluntarily) will lead to claimants losing all of their JSA for a fixed period of 13 weeks for a first failure, 26 weeks for a second failure and 156 weeks for a third and subsequent failure (within a 52 week period of their last failure).

Higher level sanction

Fixed period sanction for:Simply failing to apply for a particular job can be considered a serious breach and incur a higher level sanction, depending on the opinion of the Jobcentre Plus (JCP) adviser. Similarly, what’s ‘suitable’, or what is a ‘good reason’ for any of the things considered a breach is down to the opinion of the adviser, who can decide instantly to apply a sanction. 3 of these and people face the immediate suspension of their benefits for 3 years.

• leaving a job voluntarily without good reason

• losing a job through misconduct

• refusal/failure to apply for, or accept if offered a suitable job without good reason

• refusal/failure to participate in mandatory work activity without good reason

Even for lesser ‘offences’, penalties are draconian. Simply turning up a few minutes late to sign on can now result in the immediate imposition of a sanction – and the minimum sanction length is now 4 weeks. Commit a second of these insignificant ‘offences’ in a 12-month period and you are hit with another 4 week sanction. A third, and it increases to 13 weeks – 3 months with no income.

Commit an ‘intermediate’ offence – which means nothing more than being considered not ‘available’ enough for work, or not looking hard enough, so once again entirely dependent on the opinion of your adviser – and the first offence incurs a 13-week sanction, followed by another, and then a 26-week penalty. 6 months, based on nothing more than the opinion of a JCP adviser.

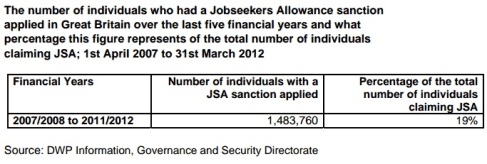

Under this government, incurring a sanction is now as easy as falling off a log – and a lot more likely. When forced to by a Freedom of Information request, the DWP admitted that as many as 19% of all claimants were sanctioned at least once:

Even this response was disingenuous, because it uses a period beginning in 2007, when sanction numbers were tiny compared to under this government, to disguise the fact that a far higher proportion of claimants are sanctioned now.

So, back to the 2006 DWP report. This was written for the DWP by Mark Peters and Lucy Joyce, examining the extent and effectiveness of sanctions applied under the Labour government – when rules for JCP advisers meant that sanctions were considered a last resort and were applied far less readily than now, when sanctions can be and are applied for something as minor as arriving a few minutes late for ‘signing on’.

In their report, Peters and Joyce included information on the proportion of claimants sanctioned 3 or more times:

data from the Sanctions Evaluation Database (SED) show that the large majority of customers (73 per cent) have only been sanctioned once, while smaller proportions have been sanctioned10% of claimants sanctioned 3 or more times - when sanctions were hard to incur. Under this government, by design, sanctions are applied freely and only require the JCP adviser to decide to apply one for it to be in force.

twice (16 per cent) or more than twice (10 per cent).

But let’s suppose, for the sake of argument, that the figure hasn’t changed, and only 10% of claimants are sanctioned 3 times or more. Based on the 778,000 sanctions applied in the year to October 2012, that means almost 80,000 people hit under the new penalty regime by sanctions of at least 3 months, and many facing 6-month and even 36-month deprivation of income.

That – though it seems incredible to call it such – is our best-case scenario. The reality is that, under the regulations that came into force in October, we could be looking at double or even triple the percentage incurring 3 or more sanctions. Even if we assumed no increase in the total number of sanctions applied, that would mean well over 200,000 people deprived of income for 3 months or longer.

And if – as seems very likely – the number of sanctions has increased by a similar proportion to the leap up to October 2012, that would mean more than 1.1 million sanctions applied, with at least 100,000 sanctions of at least 3 months and as many as 300,000.

And don’t forget, each sanction impacts not only on dependents of sanctioned people but on their family and friends, too. We could easily be looking at a million or more people impacted by summary deprivation of income.

No wonder the government decided the latest data on sanctions ‘wasn’t ready for publication’. Even many natural Tory voters would baulk at the idea of throwing a million people into either immediate penury or the burden of having to eke out already-meagre resources to prevent family members or friends from starving.

I’m frightened by it – but I’m even more incensed. I hope you are too.