Reblogged

from The SKWAWKBOX Blog:

Please share widely.

Please share widely.

In just a few short weeks, the new Universal Credit benefit system starts to

roll out, albeit more slowly than originally planned (but already in operation

in pilot areas). This new benefits system rolls a wide variety of benefits into

a single process, including unemployment benefit – and crucially, it extends

‘conditionality’ even to people who are already working, so that penalties can

be applied to people for not having enough hours, or if they are not considered

to be trying hard enough to get more hours.

The government’s ‘policy aims’ for this new system state that:

Universal Credit is designed to ensure that for

people who can, work is still the best route out of poverty and an escape from

benefit dependence. The aim of Universal Credit is to increase labour market

participation, reduce worklessness and increase in-work

progression. The conditionality regime will recast the

relationship between the citizen and the State from one centred

on “entitlement” to one centred on a contractual concept that

provides a range of support in return for claimant’s meeting an explicit set of

responsibilities, with a sanctions regime to encourage

compliance.

A series of Freedom of Information (FOI) responses from the DWP reveals that

the new regulations turn the

opinion of even junior Jobcentre

Plus (JCP) advisers into law, place them in a position of despotic omnipotence

over benefit claimants, and turn claimants – even working ones – into helpless

chattels shorn of power, choice or recourse if unreasonable expectations are

placed on them.

A ‘claimant commitment’ (CC) is a set of obligations placed on a benefit

claimant in terms of actions that must be carried out in looking for work (or

more work), the amount of time that must be spent and the results generated.

These requirements, as the DWP statement above indicates, are not negligible.

For example, as

one

of the responses states:

A claimant will be expected to devote the same number of hours to work search

in accordance with this action plan as we would expect them to be available for

work (up to a maximum of 35 hours a week).

This might seem reasonable enough. But as one ex-DWP manager asked her

MP:

Is affordability of the work search/preparation

taken into account by the Adviser? The average cost of Job seeking prior to

2012 was around £2-£6 per week assuming no job interviews secured, the Jobseeker

visited the Jobcentre once a week to look for work, checked the local press,

made 1 or 2 job applications and asked family/friends. Claimants were not

required to pay Council Tax .

£6 a week when you’re on as little as £56 a week in benefits is a huge amount

of money. But now claimants can be expected to attend the JCP more than once a

week – in fact, as often as the adviser decides is appropriate as part of the

CC. Council tax support is far less available, and the price of essentials like

food has risen steeply. The costs associated with the activities likely to be

involved in a 35-hour work-seeking week are very likely to be (to use the

government’s favourite word for NHS hospitals) unsustainable.

Claimants have a right to query the conditions of a CC – but if they refuse

to sign it and ask for it to be reviewed, it will merely be looked at by another

JCP adviser, not by a more specialised ‘Labour Market Decision Maker’

(LMDM).

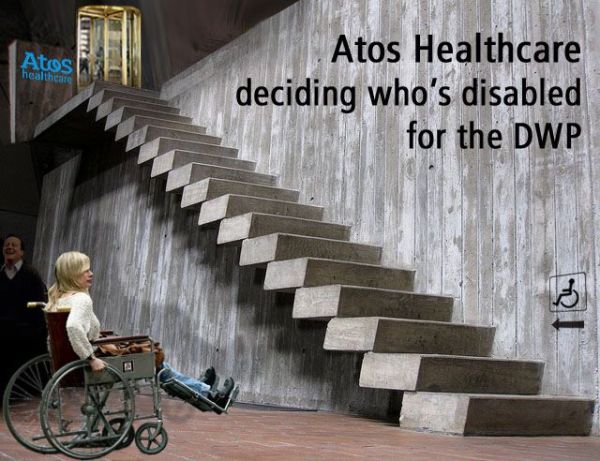

As we’re already well aware, the DWP

has

no qualms about asking JCP advisers to carry out tasks for which they have

no qualifications or experience. A decision by an adviser-level JCP employee is

perfectly likely not to take into account the full range of circumstances faced

by a claimant – and a review by another adviser, who will face his/her own

pressure to conform and not to offend a colleague or possibly incur the wrath of

a supervisor, in no way guarantees that bad decisions will be overturned.

Especially in a context in which – as we know in spite of government denials

– all of the advisers in a JCP are likely to be under pressure to meet

covert

targets on the number of sanctions the JCP applies.

But surely, if a bad CC isn’t overturned by an adviser the claimant can ask

for someone more senior to look at it? You’d think so – at least under any sane

government. However, as the 2nd FOI response makes very clear:

There is no right of appeal if

a claimant refuses to accept their Claimant Commitment and the requirements that

have been set out in it.

Under this new system, a JCP adviser – who might be incompetent,

inexperienced, bitter, have a personality clash with the claimant or just simply

be having a bad day – is the final arbiter of whether a CC is reasonable and

achievable, and even a patently bad decision cannot be appealed for a higher

opinion.

And if a claimant refuses to sign?

If the claimant still refuses to accept their

Claimant Commitment then he or she will no longer be entitled to claim

Universal Credit.

Refuse to sign something that might be realistically unachievable – and

receive nothing. Could a more coercive and arbitrary situation be imagined?

If a claimant signs and then fails or refuses to perform one of the CC

conditions, the only small ray of hope is that an LMDM might see reason:

if a claimant fails to carry out any of the work

related requirements set out in their Claimant Commitment this will be referred

to a Decision Maker for consideration of whether a sanction should be applied.

If a claimant has good reason for not carrying out a particular work related

requirement then a sanction will not be applied.

But this is asking someone to accept a set of conditions knowing they can’t

fulfil them – and then put themselves in the hands of a person whose

qualifications, motivations, reasonableness and parameters are entirely unknown,

in the hope that they’ll agree not to immediately cut off his/her benefits.

That reminds me of something. What was it? Oh, that’s right.

Russian roulette.

As the ex-JCP manager points out, the system is fraught with unknowns and

uncertainties. There is nothing in the documentation to indicate:

- what it means for a JCP adviser to ‘look again’ at a decision

- what the criteria for assessing a decision are, or how the 2nd adviser will

obtain information about the claimant’s circumstances

- whether there are any firm timescales within which the claimant commitment

review must be completed

- whether the claimant will be interviewed by the 2nd adviser or the decision

will be made entirely based on the paperwork

- whether any additional financial support is available to help claimants meet

increased work-search requirements

and I’m sure you can think of other pitfalls and problems.

We’re left with a situation in which it’s perfectly likely that someone will

be expected to sign an unrealistic CC – and summarily deprived of all financial

support if they refuse. Once coerced into signing this unrealistic commitment,

they then face a financial ‘Russian roulette’ where the whim of an unknown

person of unknown competence will decide whether a failure to comply was

‘reasonable’.

All with no guarantee, or even likelihood, that the decision will be

impartial.

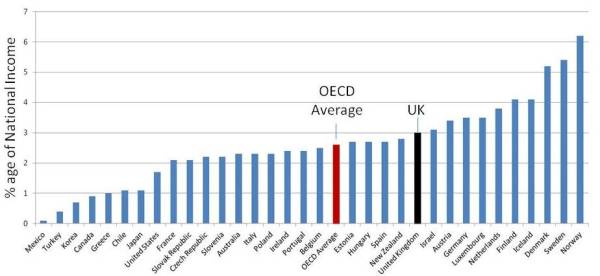

The OECD – hardly a hotbed of socialism or a great friend to the common man

or woman – considers impartiality to be very important. In a document titled ‘

Administrative

Procedures in EU Member States‘, it discussion the need for

impartiality:

5.

Impartiality

29. The principle

of impartiality is structurally weakened in administrative procedures

because the Administration is party and

judge in the procedure. Therefore it is

necessary to establish legal measures to establish the

equilibrium between the parties or at least to reduce the likelihood of

unfairness. A Minimum of impartiality should be guaranteed.

Therefore the withdrawal from the procedure of those Officials who have a

personal interest (typical conflict of interest situation) in the outcome of the

procedure 8 should be mandatory. Otherwise the

administration would incur into abuse of power. Another requirement

for impartiality is that any party in the procedure should be entitled to

recluse any intervening official suspect of having an interest in the outcome of

the procedure or having qualified friendship or enmity or kinship

relationships with any of the

parties.”

It’s absolutely obvious

that advisers working together in a JCP office will often form friendships and a

sense of loyalty to one another. It’s only human to find it difficult to judge

impartially in those circumstances, and there will be a clear pressure to ‘back

up’ one’s colleague, and a fear of upsetting a fellow adviser by overturning a

decision.

It will therefore be extremely difficult to find an impartial adviser to

judge a request for review – and even an impartial one will be judging based on

personal experience and emotion rather than on professional qualifications and

clear criteria.

In case anyone thinks ‘bloody EU and their bureaucracy’, or wants to write

off as a ‘leftie’ opinion that this situation is wrong. The Ombudsman’s office

sets out ‘

Principles

of Administration‘ that make the potential problems very clear:

The Principles of Good

Administration

Getting it

Right

Public servants do

not get it right every time, so there must be a form of redress that is

impartial and fair for claimants.

Being customer focused

Public Bodies do not always treat people with

sensitivity, bearing in mind their individual needs, and respond flexibly to the

circumstances of the case in every instance; doctors for example, can

get this wrong at times.

Acting

fairly and proportionately

Public bodies do not always deal with people fairly or

with respect.

There is no doubt at all that the new UC system completely fails to make

available an impartial and fair ‘form of redress’ as outlined by the

Ombudsman.

Let’s look at a real-life scenario. The DWP operates a

Universal Jobmatch

(UJM) system that jobseekers are expected to use to look for jobs – but the

UJM system has been shown to be seriously flawed and even a

vehicle for

various scams. It also

contains

serious security issues that risk revealing jobseekers’ private information

to people who shouldn’t have it.

Jobseekers are frequently pressured to use the system and told that they

might be sanctioned if they don’t – but our ex-JCP manager advises me that there

is

no legal obligation whatever for jobseekers to use it. They

can use any available method of jobseeking, online or offline.

Under the UC system, the

illegality of a sanction applied

for failing to use UJM

will become irrelevant. A JCP adviser

has

no legal right to apply a sanction for not using UJM – but

if they do, and a colleague

from the same JCP and therefore likely to be

similarly ill-informed agrees, then the sanctioned person has

no right of appeal.

Yet again the government, via its ludicrously corrupt and vicious Department

of Work and Pensions’ is showing a staggering degree of contempt for those in

society who need help and support, and a complete disregard for the life and

wellbeing of

human beings in our society who find themselves in

need of that support.

Support which, as the government baldly states, is no longer the

‘entitlement’ it should be in a civilised society, but is instead something for

which people are forced to sign unfeasible contracts that merely set them up to

have that support snatched away arbitrarily – on the ‘godlike’ whim of JCP

advisers of unknown competence and who might well be under pressure to hit

sanction targets.

And all, if we’re to believe this lying-if-their-lips-are-moving government,

because it’s the best ‘route out of poverty’.

Yeah. Like the best cure for a headache is decapitation.

Many, many people in this country will not survive a 2nd term of this

government, or any part of it. And the way the rules are constructed shows that

the Tories are ‘perfectly relaxed’ about that.

They want to take us back to the 1920s of soup kitchens, means-testing and

stigmatised poverty.

We can’t let them. Please spread the word or this is where we’ll end up

again: