The destructive power of state snooping is on display for all to see. The press must not yield to this intimidation

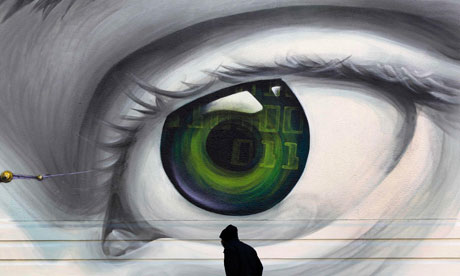

'But it remains worrying that many

otherwise liberal-minded Britons seem reluctant to take seriously the abuses

revealed in the nature and growth of state surveillance.' Photograph: Yannis

Behrakis/Reuters

You've had your fun: now

we want the stuff back. With these words the British government embarked on the

most bizarre act of state censorship of the internet age. In

a Guardian basement, officials from GCHQ gazed with satisfaction on a pile of

mangled hard drives like so many book burners sent by the Spanish

Inquisition. They were unmoved by the fact that copies of the drives were

lodged round the globe. They wanted their symbolic auto-da-fe. Had the Guardian

refused this ritual they said they would have obtained a search and destroy

order from a compliant British court.

Two great forces are now

in fierce but unresolved contention. The material

revealed by Edward Snowden through the Guardian and the Washington Post is

of a wholly different order from WikiLeaks and other recent

whistle-blowing incidents. It indicates not just that the modern state is

gathering, storing and processing for its own ends electronic communication from

around the world; far more serious, it reveals that this power has so corrupted

those wielding it as to put them beyond effective democratic control. It was not

the scope of NSA surveillance that led to Snowden's defection. It was hearing

his boss lie to Congress about it for hours on end.

Last week in Washington,

Congressional investigators discovered that the America's foreign

intelligence surveillance court, a body set up specifically to oversee the

NSA, had

itself been defied by the agency "thousands of times". It was victim to "a

culture of misinformation" as orders to destroy intercepts, emails and files

were simply disregarded; an intelligence community that seems neither

intelligent nor a community commanding a global empire that could suborn the

world's largest corporations, draw up targets for drone assassination, blackmail

US Muslims into becoming spies and haul passengers off planes.

There is clearly a case for prior censorship of some matters of national security. A state secret once revealed cannot be later rectified by a mere denial. Yet the parliamentary and legal institutions for deciding these secrets are plainly no longer fit for purpose. They are treated by the services they supposedly supervise with falsehoods and contempt. In America, the constitution protects the press from pre-publication censorship, leaving those who reveal state secrets to the mercy of the courts and the judgment of public debate – hence the Putinesque treatment of Manning and Snowden. But at least Congress has put the US director of national intelligence, James Clapper, under severe pressure. Even President Barack Obama has welcomed the debate and accepted that the Patriot Act may need revision.

In Britain, there has been

no such response. GCHQ could boast to its American counterpart of its "light

oversight regime compared to the US". Parliamentary and legal control is a

charade, a patsy of the secrecy lobby. The press, normally robust in its

treatment of politicians, seems cowed by a regime of informal notification of

"defence sensitivity". This D-Notice system used to be confined to

cases where the police felt lives to be at risk in current operations. In the

case of Snowden the D-Notice has been used to warn editors off publishing

material potentially embarrassing to politicians and the security services under

the spurious claim that it "might give comfort to terrorists".

Most of the British press

(though not the BBC, to its credit) has clearly felt inhibited. As with the

"deterrent" smashing of Guardian hard drives and the harassing

of David Miranda at Heathrow, a regime of prior restraint has been

instigated in Britain whose apparent purpose seems to be simply to show off the

security services as macho to their American friends.

There is no conceivable

way copies of the Snowden revelations seized this week at Heathrow could aid

terrorism or "threaten the security of the British state" – as charged today by

Mark Pritchard, an

MP on the parliamentary committee on national security strategy. When the

supposed monitors of the secret services merely parrot their jargon against

press freedom, we should know this regime is not up to its job.

The war between state power and those holding it to account needs constant refreshment. As Snowden shows, the whistleblowers and hacktivists can win the occasional skirmish. But it remains worrying that many otherwise liberal-minded Britons seem reluctant to take seriously the abuses revealed in the nature and growth of state surveillance. The arrogance of this abuse is now widespread. The same police force that harassed Miranda for nine hours at Heathrow is the one recently revealed as using surveillance to blackmail Lawrence family supporters and draw up lists of trouble-makers to hand over to private contractors. We can see where this leads.

I hesitate to draw parallels with history, but I wonder how those now running the surveillance state – and their appeasers – would have behaved under the totalitarian regimes of the 20th century. We hear today so many phrases we have heard before. The innocent have nothing to fear. Our critics merely comfort the enemy. You cannot be too safe. Loyalty is all. As one official said in wielding his legal stick over the Guardian: "You have had your debate. There's no need to write any more."

Yes, there bloody well is.

Guardian